I get the idea that foreign or classic car owners on the coasts often have “a guy” to help them out of trouble when things start to fall apart. For instance, my dad, when he was piecing together his 1973 3.0 CS, had most of the work done at shops within a 15 mile radius of our house in York, PA. To have the carbs tuned, he sent the car down the road to the shop with plenty of Alfas out front. For upholstery, he commissioned a shop downtown with a slew of Grand Wagoneers in the lot, and, at one point etched into my memory, a Watusi bull in various stages of meat grinding inside the shop. To get the brakes ready for inspection, he dropped the car off behind a trailer park, close to the river. He kept the car in shape without ever leaving York County.

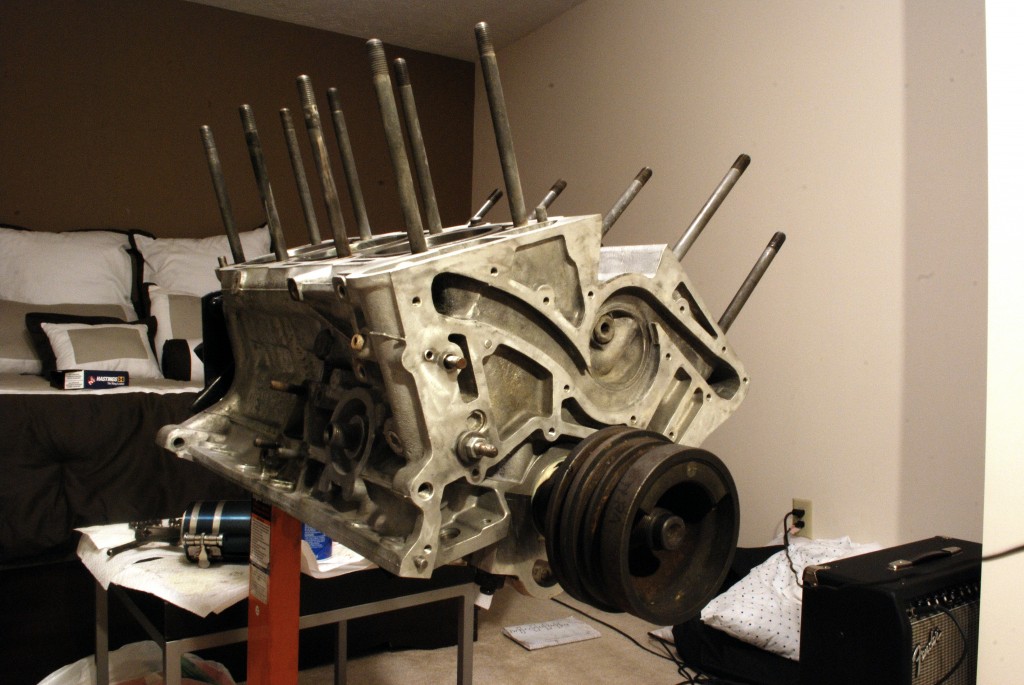

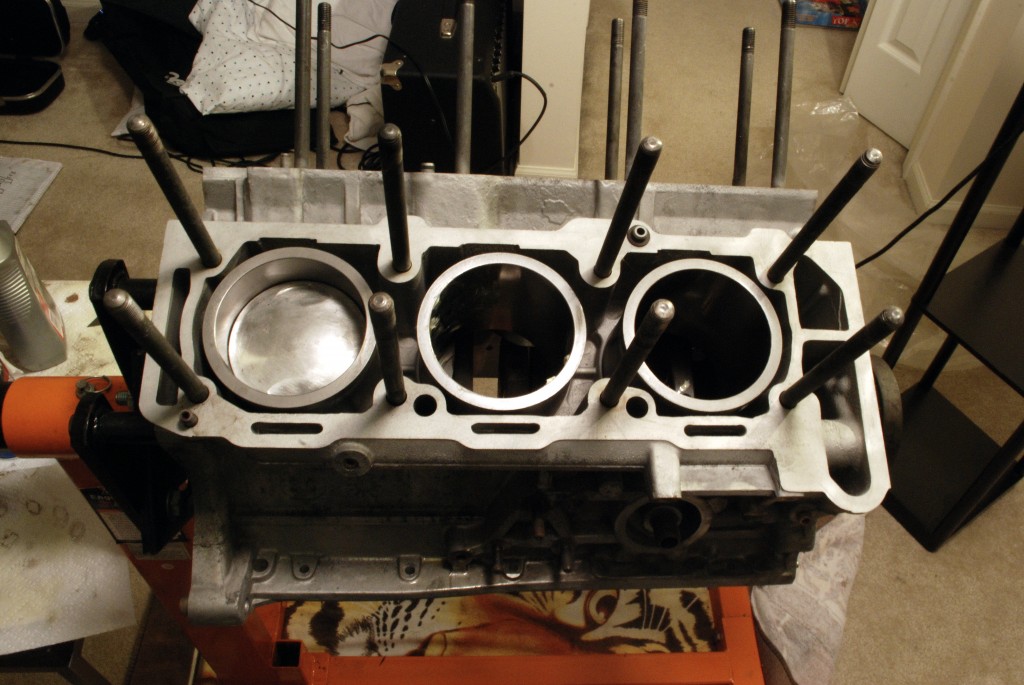

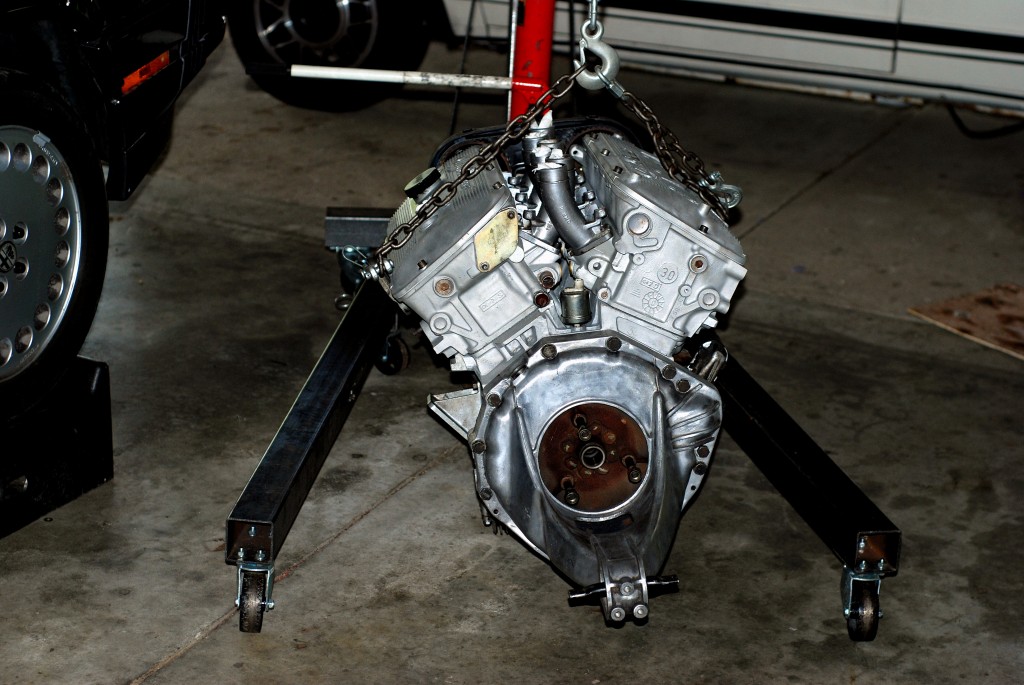

Living in Columbus, IN, undertaking an Alfa V6 rebuild posed some geographical challenges. The only European shop in the county was the local Import Auto shop, where I buy all of my VW and BMW parts. So, for ignition and fuel system components, I had the convenience of stopping by after work to pick up parts. I asked around for recommendations on local machine shops, and drove south to Jackson County, where I found a shop for head work, and a shop to take care of the bottom end.

Some cultural challenges found their way into the mix. First, there was the lengthy debate at the bottom end shop, wherein I had to convince the shop owner that my Alfa V6 really wasn’t related to a Ford V6. We agreed that he was confusing Alfa with Jag, and moved on, unphased. But then, he became adamant that we would need to remove the head studs, which are permanent fixtures from the day they roll off of the line in Arese. I’d never built an Alfa V6, or any engine of my own, at this point, so I had to pay close attention to his plans for the bottom end, gingerly asserting my 2 months of Alfa research against his 30 years of American V8 builds when necessary. I didn’t doubt this guy’s mass of experience building race motors (engines), but mechanical confidence usually leads to explosions, fires, and failures, in my experience.

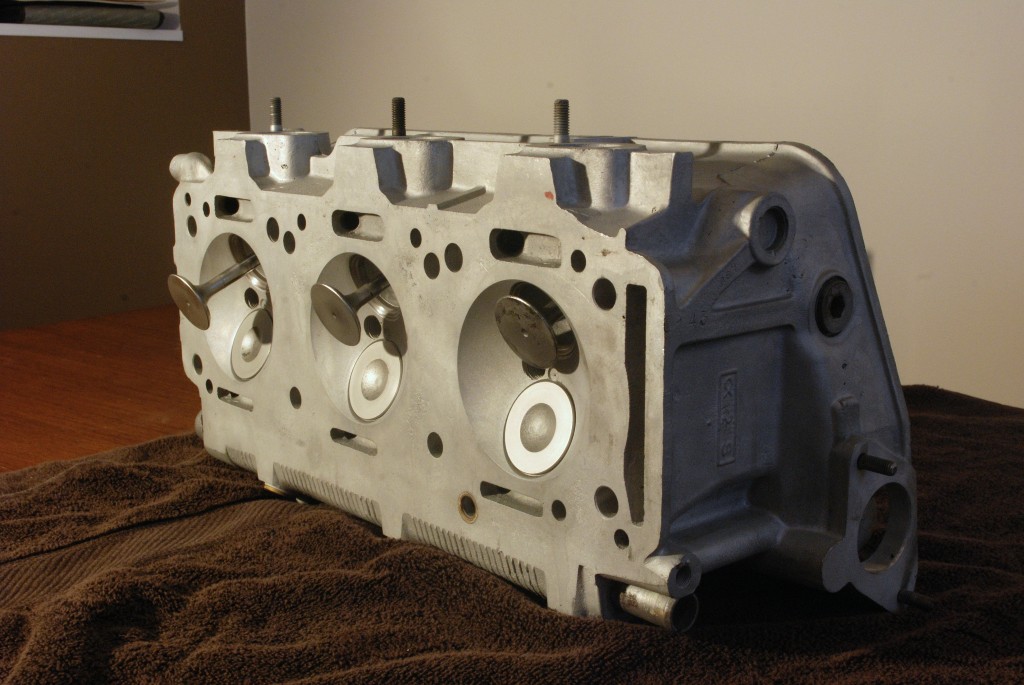

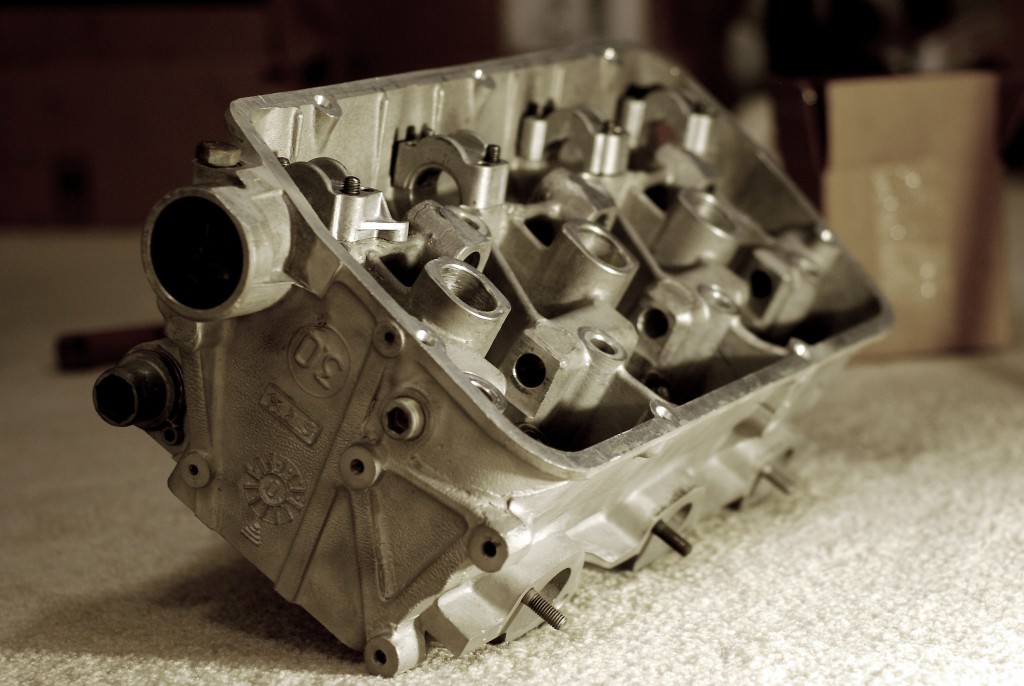

The head guy handily surpassed the block guy on the confidence scale. I’m talking all-American, dad-approves-of-my-choices, quarterback-since-third-grade confidence. His certainty cost me two weeks of build time (this was back when I was actually moving swiftly on the build), and all he managed to do was hot tank the heads. He didn’t have the right reamer to do exhaust valve guides, he did a poor enough job grinding the valve seats that I had them redone, and he left blasting media in every possible oil and coolant passageway. He really wanted to take material off the valve tips to set the lash for me, not realizing that the surface-hardening would be lost and result in mushrooming. I think I saw him wipe his hand on his work apron after I shook his hand and walked my heads out.

Fortunatley, I found a shop to take over the heads up in Indy. Expecting the worst, I was reassured when the machinist stayed an hour after the shop closed to walk through the specs with me. I haven’t run the heads yet, but I’m looking forward to the results of his work – hopefully in the form of intoxicating induction growl.

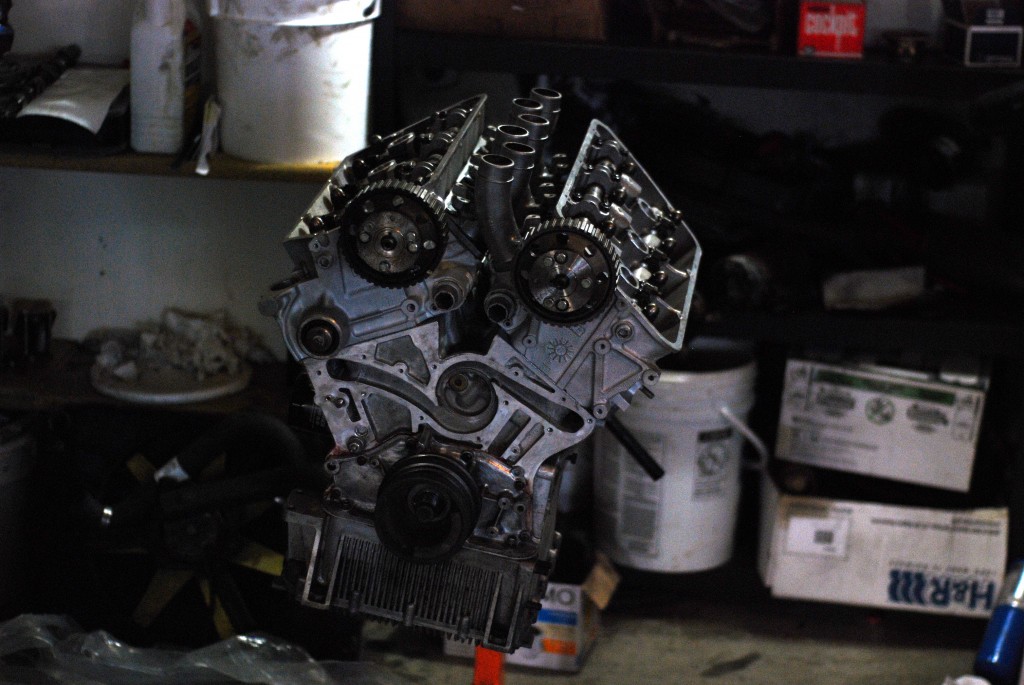

Disassembling the heads was easy – I just placed a deep-well socket onto the valve retainers and popped them with a mallet. As I began to reassemble the heads, I couldn’t come up with a decent tool to compress the valve springs, which sit inside the tappet bores, so I ended up borrowing the Alfa Romeo service tool. I basically had to sit on the heads to keep them from rotating while I applied force to the service tool, so I felt pretty ragged the next morning.

I had reservations about running my Verde oil pump, but after sending it to an Alfa/Ferrari race shop in Chicago, I was sure that the components were all within spec and worth running. For added security, I requested a new pressure relief valve spring, which the shop has impressively sourced. They even reengineer the relief valve pistons, which is quite the engineering/metallurgical/manufacturing feat, considering the importance of oil pressure, and the myriad parameters that a small shop has to get right to succeed in their design.

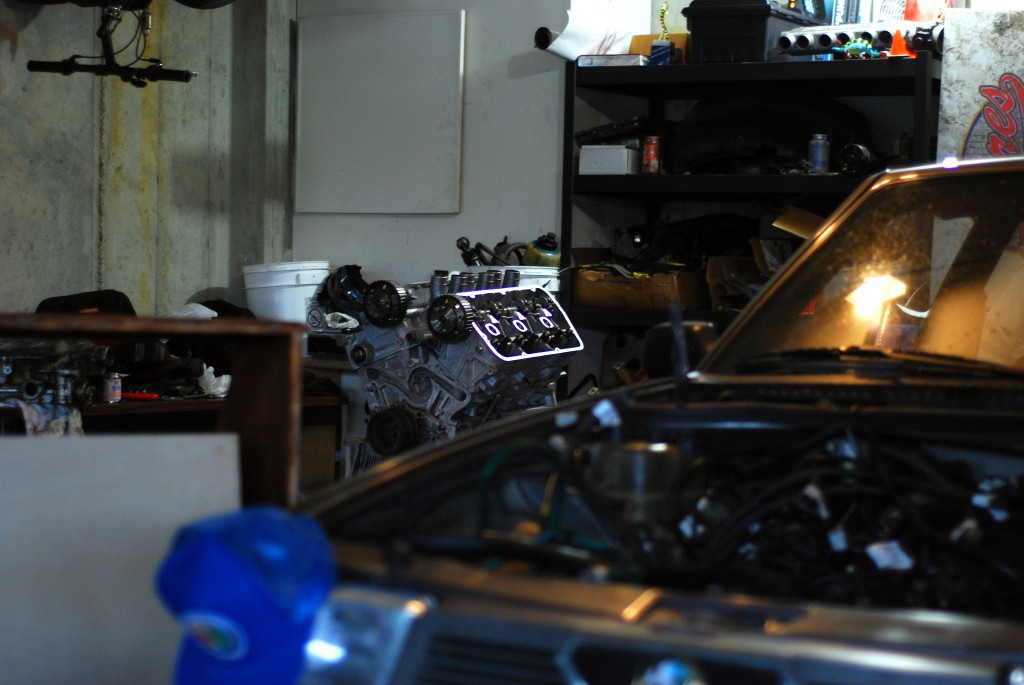

Once I had a long block assembled, I set about timing the engine and installing the water pump. I immediately stripped the timing belt tensioner mounting stud, and wasn’t able to pull the sucker with some jam nuts. My stud puller tool also failed, shearing the stud flush with the surface of the block. I drilled into the stud and attempted to pull it with an extractor, which, of course, sheared inside of the stud. Damnit, Graham. I grabbed another Hamm’s, and reflected on my life and my choices. After consulting future technical specialist Malhon, I bought some diamond burr dremel bits and a tungsten carbide dremel bit, since I’d need to demolish some unfortunately hardened tool steel. I enjoyed the glowing of the heat soaked extractor as I ground my way through it (using grease to contain as much of the shavings as possible). I ground as much of the stud out and then used a larger extractor, which, thankfully, resulted in the most satisfying separation of a 30-year-old union that I’ve ever experienced.

I’m fully aware of how dull it is to read about some hack dealing with broken studs, but I don’t think I will take a single drive in that car without thinking back on how totally gone that stud was, and how I held off on taking the long block to a machine shop for a rescue. I even keep a trophy rack of destroyed hardware, because as difficult as a proper rebuild can be, it’s the broken hardware that takes the most effort. Inventors are still developing tools and devices to get mechanics out of the most dreaded situations, and the shop manuals sure as hell do not cover stripped stud removal or tool steel destruction.

The rest of the process was relaxing. Timing a 12V Alfa is quite enjoyable and efficient in comparison to the nightmare of a job that the 24V timing belt presents. And, after taking so much care to ensure the mechanical future of all of the internal components, it was a relief to be able to snug up the socket head cap screws on the valve covers and conceal the project with the beautiful Alfa Romeo script.

I dropped the engine into the car when I was at home by myself, which wasn’t as painful as I expected it to be. The driveshaft and shift linkage are connected; the DeDion suspension is once again mated to the chassis. I just need to address air, fuel, and some wiring, and hopefully the car will be running soon after I tow it back to Michigan. Simple enough, but it’s an Alfa, and I’m not a professional, so I’m sure that my mechanical patience will be tested again in the very near future.